Ladislaus Lob, "Christian Dietrich Grabbe," Encyclopedia of German Literature [Konzett, Matthias, ed.], Routledge (2015), p. 362-3:

In German cultural history, Christian Dietrich Grabbe's work coincides with the Biedermeier period, the transitional phase between the end of classicism and Romanticism on the one hand and the rise of realism on the other. In the context of German political history, it falls into the "Restauration" or Vormärz" era, which began with the defeat of Napoléon in 1815 and closed with the revolutions of March 1848. Sigmund Freud described Grabbe as "an original and rather peculiar poet," Heinrich Heine called him "a drunken Shakespeare," and Karl Immermann saw him as having both "a wild, ruined nature" and "an outstanding talent." Although his image as a flawed genius lingers, he is now also hailed as one of Germany's major experimental dramatists, and the irregularities of his plays are regarded as an integral part of their originality.

The only child of the local jailer, Grabbe felt oppressed and alienated in his provincial hometown of Detmold where, as he wrote to Ludwig Tieck, "an educated person is looked upon as an inferior kind of fattened ox." Physically frail and psychologically unstable, he seemed the archetype of the dissolute bohemian artist, oscillating between sullen shyness and aggressive self-assertion, imperiously demanding recognition but refusing to please or to conform, performing erratically in his duties as army legal officer, staying in a destructive marriage, and precipitating his fatal decline by excessive drinking. While it is uncertain to what extent his "bizarreness" was natural and to what extent it was cultivated to shock his middle-class contemporaries, the "Grabbe myth" soon become confused with, and has often overshadowed, his work.

After his death, Grabbe was condemned to oblivion by classically oriented criticism, until both the nationalists and naturalists of the late 19th century rediscovered him as a kindred soul. In the 20th century, the Expressionists celebrated him as a fellow outcast of bourgeois society, the Dadaists and surrealists welcomed him as another rebel against rationality, the Nazis exalted him as a prophet of "blood and soil," Brecht placed him alongside Georg Büchner in the "non-Aristotelian" tradiiton leading from the Elizabethans to his own Marxist "Epic Theater," and more recent commentators have stressed his affinities with postmodernism.

[...]

By consesus Grabbe's supreme achievement consists of his innovations in historical drama. Unlike the historical plays of Schiller and his followers, which were classical in style and idealistic in character, Grabbe's historical plays are prosaic in language, episodic in structure, and realistic in outlook. Above all, they present history as determined not by abstract ideas or outstanding personalities but by mass movements and the contingencies of time, place, circumstance and chance. [...] Speaking of Napoleon, he rightly claimed to have accomplished "a dramatic epic-revolution," although he might well have included his other historical plays in that remark.

Grabbe's "revolution" in historical drama was accompanied by a revolutionary approach to drama in general. Once dismissed as signs of incompetence, capriciousness, or a sick psyche, his methods now seem eminently modern. Full of incongruities and distortions, deliberately avoiding any appearance of harmony or beauty, his disjointed actions, ambiguous characters, dissonant dialogue, and tragicomic moods not only reflect the social, intellectual, and aesthetic tensions of his own age but also anticipate the "open" form and "absurd" content favoured by many dramatists in ours. Long before the cinema was invented, he also foreshadowed many of its techniques.

|

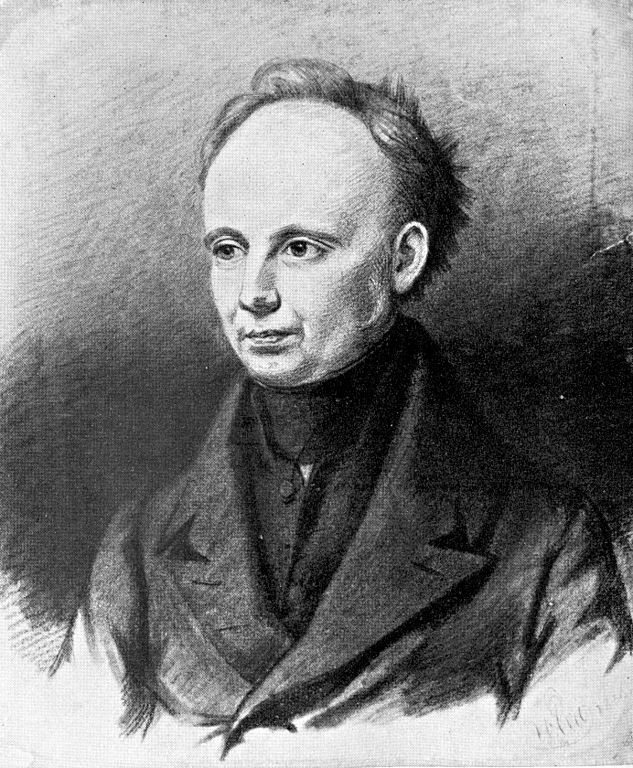

Christian Dietrich Grabbe (1801-1836), lithograph by W. Severin after a drawing by Joseph Wilhelm Pero (1808-1862) |

NB: Christian Dietrich Grabbe's life was dramatized by Hanns Johst in

Der Einsame [

The Loner] in 1917. Brecht wrote

Baal in response the following year.